What is Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (C-PTSD)?

What Is Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (C-PTSD):

Understanding the Condition, Symptoms, Risk Factors, and Treatment Options

Written by Alex Penrod, MS, LPC, LCDC - Licensed Professional Counselor in the state of Texas and Certified Clinical Trauma Professional II

Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (C-PTSD) is a condition that can develop in response to prolonged, repeated exposure to traumatic events, particularly those occurring during early developmental years or in situations where escape is difficult or impossible. It differs from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in its causes, symptoms, and treatment needs, and it is especially relevant for survivors of childhood abuse, domestic violence, catastrophic experiences, or captivity.

Just as one rock thrown into a pond will create some ripples, many rocks thrown in or a prolonged storm will create larger waves, crashing into each other in confusing and overwhelming ways. This can make it extremely difficult to regulate emotions on such choppy waters, distorts the way we see ourselves in the reflection, and interferes with out ability to engage with others and maintain relationships when we are just trying to hold on without capsizing.

Organizations such as the International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation (ISSTD) have long recognized complex trauma and developmental trauma disorder as distinct entities requiring more tailored treatment strategies versus those for PTSD. However, C-PTSD was only recently recognized as a diagnosis in the International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision (ICD-11), which came into effect in 2022.

This page provides an overview of the ICD-11 diagnosis of C-PTSD, including:

Definition of C-PTSD

Distinctions between PTSD and C-PTSD

Symptoms

Diagnostic Criteria

Controversy

Risk and Protective Factors

Prevalence Among Various Populations

Common Co-Occurring Disorders

Evidence-Based Treatments

Recovery Rates

Definition of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (C-PTSD)

Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (C-PTSD) arises from chronic or long-term exposure to traumatic events which can have profound impacts on the brain and nervous system. Unlike PTSD, which can develop after a single traumatic event, C-PTSD is typically associated with ongoing trauma, such as childhood abuse, severe neglect, physical abuse and domestic violence, human trafficking, or situations of captivity. It involves all the symptoms of PTSD, as well as additional symptoms related to emotional regulation, self-concept, and interpersonal relationships.

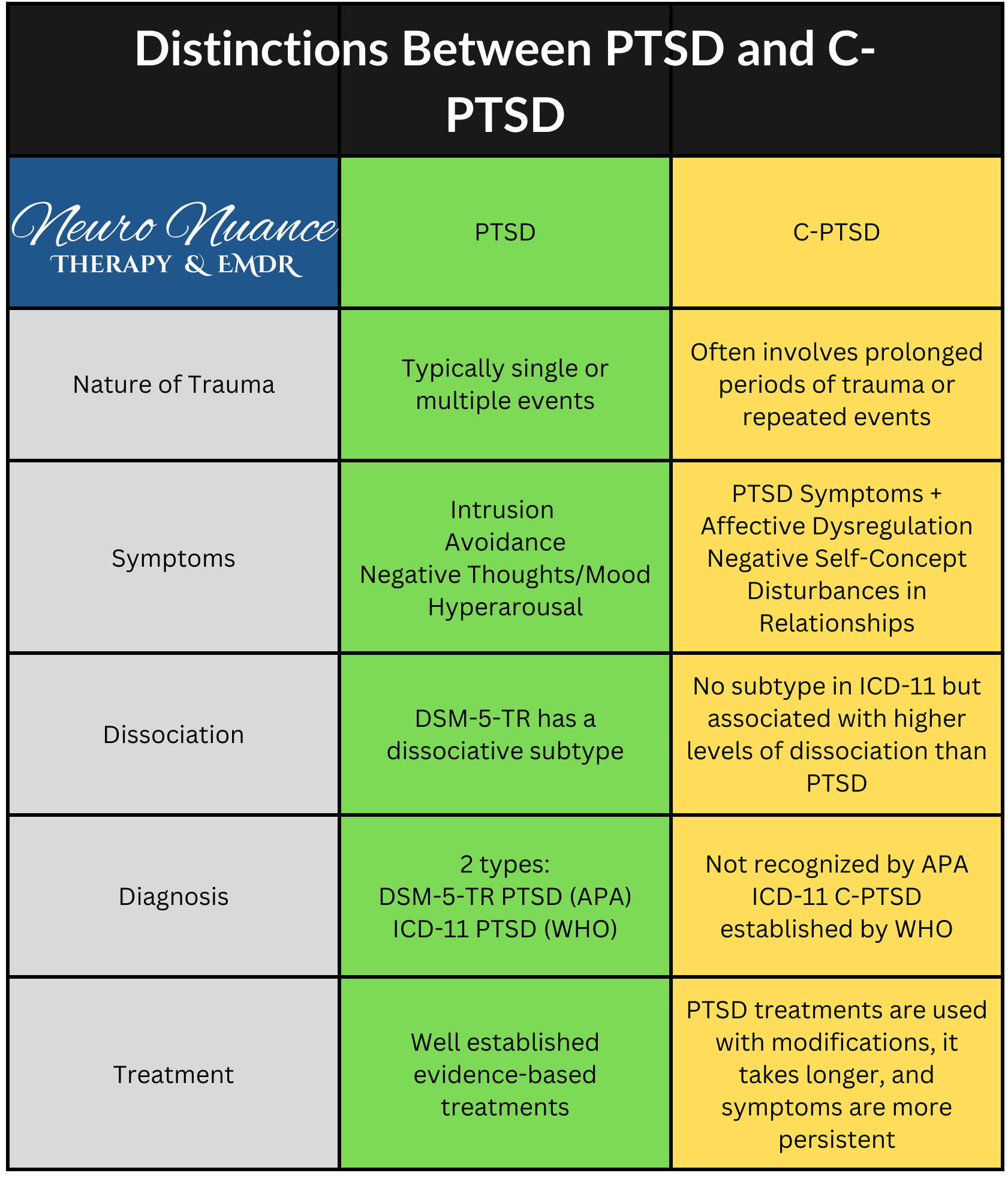

Distinctions Between PTSD and C-PTSD

While both PTSD and C-PTSD arise from traumatic experiences, several key differences distinguish these two conditions:

Nature of Trauma:

PTSD: Often results from a single, short-term traumatic event such as a car accident, natural disaster, or assault.

C-PTSD: Typically develops from chronic trauma that occurs over months or years, especially situations of early trauma, child abuse, or within contexts where the victim feels trapped or powerless (e.g., domestic violence, captivity).

Symptom Complexity:

PTSD: Symptoms focus primarily on re-experiencing the trauma (flashbacks, nightmares), avoidance behaviors, negative thoughts and mood changes, and hyperarousal.

C-PTSD: Includes all PTSD symptoms, plus additional symptoms such as difficulty with affect regulation, persistent negative self-perception, difficulties in relationships, and feelings of helplessness or hopelessness.

Interpersonal Difficulties:

PTSD: May lead to strained relationships due to avoidance and hyperarousal but does not necessarily impact core self-identity.

C-PTSD: Often leads to significant difficulties in forming and maintaining relationships, a pervasive feeling of isolation, and distorted beliefs about oneself leading to a negative self-view (e.g., sense of worthlessness and feelings of shame that go beyond low self-esteem).

Diagnosis and Treatment:

PTSD: Diagnosis is more well-established with a clear set of criteria in the DSM-5-TR. Treatment often focuses on trauma-specific therapies.

C-PTSD: Recognized in the ICD-11 but not specifically in the DSM-5-TR, and treatment is more complex due to the need to address developmental and relational trauma aspects.

Symptoms of C-PTSD

The symptoms of C-PTSD can be grouped into three core categories beyond those seen in PTSD:

Affective Dysregulation:

Persistent difficulty managing emotional responses (e.g., intense strong emotions of sadness, anger, or fear, etc.).

Episodes of emotional numbness or feelings of detachment from one's emotions (e.g., feeling "shut off").

Negative Self-Concept:

Deep-seated feelings of worthlessness, shame, or guilt.

Persistent core beliefs of being "damaged" or "different" from others.

Interpersonal Difficulties:

Problems in forming and maintaining close relationships.

Difficulty trusting others and feeling emotionally close to others.

Tendency toward social isolation or seeking out relationships that replicate past trauma.

Diagnostic Criteria for C-PTSD

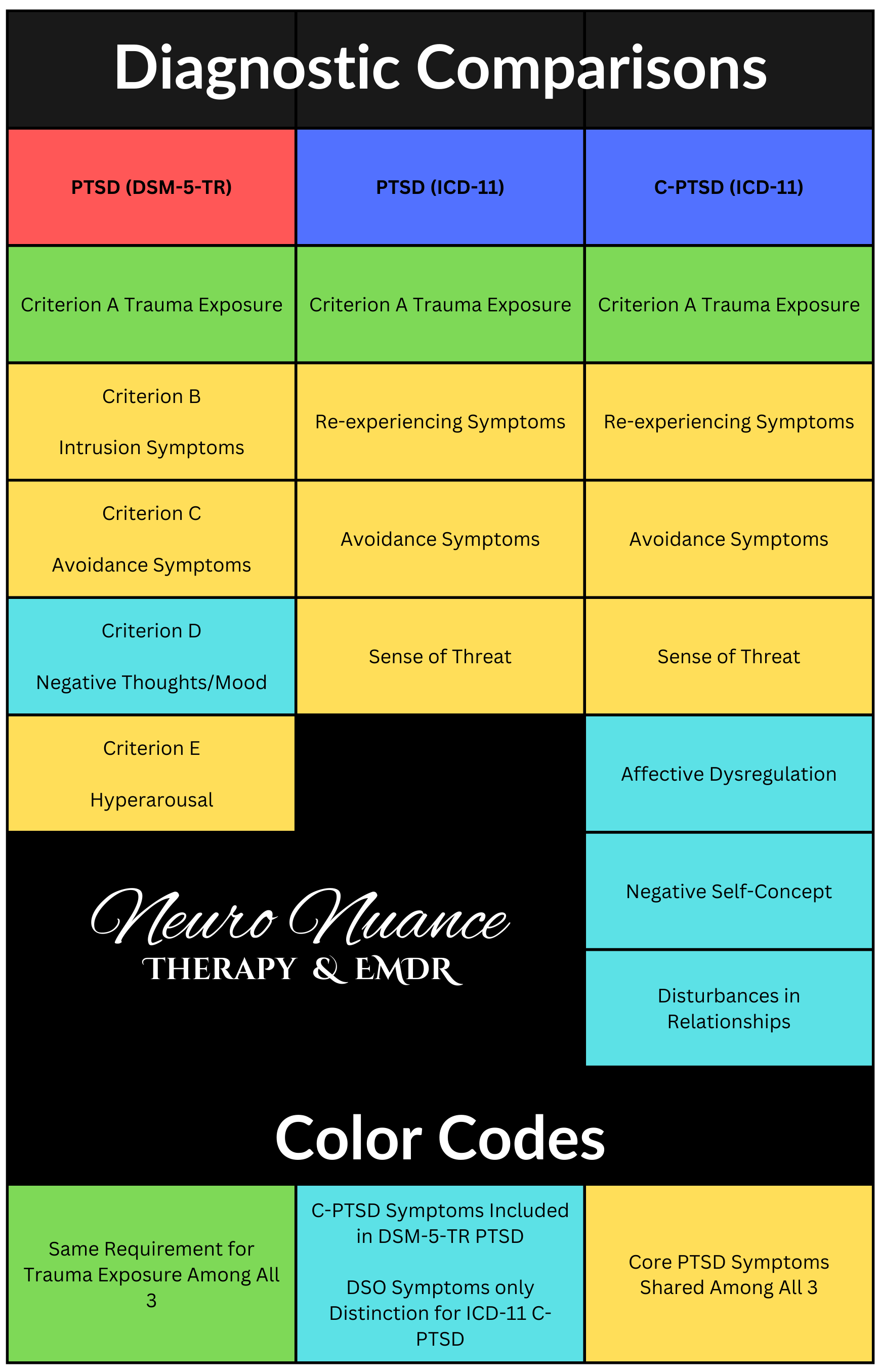

While C-PTSD is not explicitly listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR), it is recognized in the International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision (ICD-11). The ICD-11 outlines the following criteria for a mental health professional to diagnose C-PTSD:

Criterion A Event: just like PTSD, C-PTSD requires that an individual has witnessed, experienced, or been threatened with death, serious injury, or sexual violence.

Core Symptoms of PTSD: All criteria for ICD-11 PTSD must be met (e.g., re-experiencing intrusive memories, avoiding reminders of the trauma, and heightened arousal)

The defining symptoms of complex PTSD are referred to as Disturbances of Self-Organization (DSO) symptoms:

Affective Dysregulation: Severe and persistent difficulty regulating emotions.

Negative Self-Concept: Deep feelings of guilt, shame, or worthlessness, often linked to the trauma.

Interpersonal Relationship Difficulties: Problems maintaining healthy, trusting relationships, often resulting in feelings of isolation or conflict.

The duration of symptoms must be at least six months and cause significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

Controversy

American psychiatrist, Judith Herman, MD, introduced the diagnosis of C-PTSD in 1992. From the outset it was met with resistance due to skepticism that it truly reflects a separate condition or separate diagnosis. Herman felt that the diagnosis of PTSD didn't fully capture the set of symptoms and complex reactions she observed in survivors of chronic, interpersonal, and childhood trauma. Although it took a long time, her influence did effect change, but not in any kind of coherent way. It resulted in two totally different strategies:

In 2013, The American Psychiatric Association (APA) released the DSM-5, which expanded the diagnostic criteria for PTSD to include symptoms identified by Herman, essentially lumping PTSD and C-PTSD into the same diagnosis by creating room for C-PTSD.

In 2022, The World Health Organization (WHO) released the ICD-11 which created a separate diagnosis of C-PTSD by adding the DSO symptoms (blue) which must be present in addition to meeting criteria for ICD-11 PTSD.

Important to note is that neither approach recognizes a difference in the type of trauma required. The bar for C-PTSD is the same as PTSD regarding what kind of trauma is "severe" enough. The distinctions in both diagnostic systems are focused on the symptom profile of C-PTSD. The United States (APA) and Europe (WHO) both appear to agree that a PTSD diagnosis is reserved for survivors of severe "big T trauma" despite the common misconception that C-PTSD reflects a culmination of "little t traumas" such as emotional abuse. This makes little difference to trauma therapists who see the damaging effects of “little t traumas” like emotional abuse everyday, but diagnosis is big business and the implications of a lower threshold for diagnosis could cost significant amounts of money for healthcare systems. Read more on this from the National Center for PTSD.

Although it seems Herman was somewhat validated by these diagnostic updates, there is still little consensus in the behavioral health field and we now have two different versions of PTSD making research a bit complex. The American Psychiatric Association and American Psychological Association do not recognize C-PTSD as a diagnosis and some argue C-PTSD reflects PTSD combined with the enduring personality changes seen in borderline personality disorder (BPD). A systematic review of current evidence shows there are distinctions between C-PTSD and BPD, and there is clinical utility of the C-PTSD diagnosis in the ICD system, but not so much for the DSM system.

The good news is that with or without a formal diagnosis, trauma-focused psychotherapists have been recognizing the differences between PTSD and C-PTSD and following Herman's best practices and treatment guidelines for decades. If all of this is making your head hurt, you’re not alone. Therapists would much rather work on helping people heal than split hairs over symptoms and argue with each other. We leave that for the academics, politicians, and businessmen in the field.

Risk Factors for Developing C-PTSD

Several factors can increase the risk of developing C-PTSD following chronic trauma:

Types of Trauma and Duration:

Repeated exposure and long-term trauma (e.g., childhood abuse, domestic violence) increases the risk.

Situations where the individual feels trapped, powerless, or unable to escape (e.g., captivity, community violence, trafficking).

Developmental Stage During Trauma:

Trauma occurring in early childhood or adolescence, a critical period for emotional, social, and attachment style development, heightens vulnerability.

Lack of Social Support:

Limited support from family, friends, or community following the trauma can increase the risk.

Pre-existing Mental Health Issues:

A personal or family history of mental health disorders, such as depression or anxiety, increases susceptibility.

Dissociation During Trauma:

Experiencing dissociative states during trauma is linked to a higher risk of developing C-PTSD.

Protective Factors Against C-PTSD

Certain factors can help reduce the risk of developing C-PTSD or mitigate its severity:

Strong Social Support Network: Support from friends, family, and the community can provide emotional and practical assistance.

Access to Mental Health Resources: Early intervention with trauma-informed care can reduce the risk or severity of symptoms.

Resilience and Coping Skills: Positive coping mechanisms, such as mindfulness, grounding techniques, and emotional regulation skills, can help manage stress and trauma.

Stable Environment Post-Trauma: A safe and nurturing environment after the trauma can provide a foundation for recovery.

Prevalence of C-PTSD Among Various Populations

C-PTSD can affect anyone exposed to prolonged trauma, but certain populations are more at risk:

Survivors of Childhood Abuse: Individuals who experienced physical, emotional, or sexual abuse during childhood have a high risk of developing C-PTSD.

Domestic Violence Survivors: Those who experience prolonged intimate partner violence or sexual assault often develop symptoms of C-PTSD.

Refugees and Asylum Seekers: Individuals who have faced prolonged persecution, torture, or displacement may experience C-PTSD.

Human Trafficking Victims: People subjected to prolonged exploitation or captivity are at significant risk.

Military Personnel: While PTSD is common, some military personnel exposed to prolonged combat or captivity may develop C-PTSD.

Common Co-Occurring Disorders with C-PTSD

C-PTSD often coexists with other psychological disorders and mental health conditions and can lead to the development of other mental health problems, complicating diagnosis and treatment:

Depression: Major depressive disorder is common among individuals with C-PTSD, often linked to feelings of hopelessness or worthlessness. C-PTSD can make people especially prone to suicidal thoughts due to the intense and enduring negative self-concept. Depression may also be accompanied by somatic physical symptoms.

Anxiety Disorders: Generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and social anxiety frequently co-occur with C-PTSD.

Substance Use Disorders: Individuals with C-PTSD may use substances as a way to cope with emotional pain and trauma.

Dissociative Disorders: Dissociative identity disorder (DID), depersonalization, or dissociative amnesia can co-occur with C-PTSD, particularly in cases of severe, chronic trauma.

Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD): Some individuals with C-PTSD exhibit similar symptoms that overlap with BPD, such as emotional dysregulation, unstable relationships, and impulsivity. However, BPD has differentiating symptoms of its own that can be distinguished.

Evidence-Based Treatments for C-PTSD

Treatment of complex PTSD involves addressing both PTSD symptoms and additional symptoms related to emotional regulation, self-concept, and relational difficulties. Trauma-focused therapy is different from talk therapy in crucial ways highlighting the importance of finding a therapist specialized in trauma. Evidence-based treatments and trauma-focused therapies include:

Phase-Oriented Trauma Therapy:

Treatment is often approached in phases, focusing first on establishing safety, stabilizing symptoms, and building coping skills before addressing traumatic memories.

Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT):

Trauma-Focused CBT can help individuals reframe and process traumatic memories and develop healthier coping mechanisms. Modifications are often needed for C-PTSD to address developmental and relational trauma aspects.

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR):

EMDR is effective for processing traumatic memories but may need to be adapted for C-PTSD to include preparation phases that focus on emotional regulation and stabilization of dissociative symptoms.

Prolonged Exposure Therapy (PE):

PE helps individuals desensitize trauma memories through gradually increased exposure, reducing avoidance behaviors and PTSD symptoms.

Narrative Exposure Therapy (NET):

NET involves creating a chronological narrative of a person's life, integrating traumatic experiences with the goal of reducing trauma-related symptoms.

Pharmacotherapy:

Medications such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI’s) can help manage co-occurring symptoms of depression and anxiety. Other medications may be considered for specific symptoms. Consult with a licensed prescriber for more options. The information contained here is not meant for anything other than educational purposes and does not constitute advice or a recommendation for medical treatment of any disease or condition.

Recovery Rates for C-PTSD

Recovery from C-PTSD varies widely depending on factors like the severity, duration, and type of trauma, individual resilience, and access to effective treatment. While recovery can be a long-term process beyond what is typical of PTSD, research suggests that with appropriate, trauma-informed care, many individuals can experience significant symptom reduction and improvement in quality of life.

Short-term Recovery: Initial phases of treatment often focus on stabilization and managing acute symptoms, such as flashbacks, anxiety, and emotional dysregulation. During this phase, patients may experience a reduction in immediate distress and develop better coping mechanisms.

Long-term Recovery: Full recovery from C-PTSD often requires a multi-year commitment to therapy, especially for those with deep-seated relational and self-concept issues. However, with sustained treatment, many individuals show marked improvement in emotional regulation, self-esteem, and interpersonal functioning.

Recovery Maintenance: Even after successful treatment, individuals with C-PTSD may be vulnerable to triggers or stressors that can cause a return of symptoms. Ongoing support, such as periodic therapy sessions or involvement in support groups, can help maintain recovery.

Conclusion

Complex Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (C-PTSD) is a severe, often debilitating condition that requires a comprehensive, trauma-focused approach to treatment. Understanding the unique symptoms, risk factors, and treatment needs is crucial for effective intervention. With early diagnosis, evidence-based therapies, and strong support systems, individuals with C-PTSD can achieve significant recovery, rebuild their lives, and restore a sense of safety, trust, and self-worth.

As a take-away, I’d like to emphasize that although the various authorities in the mental health field can’t seem to agree on C-PTSD, trauma-focused psychotherapists have been recognizing and honoring the differences without the diagnosis for decades. People deserve healing regardless of how academics would like to label them. To learn more about me and my approach to treating C-PTSD consider visiting my home page, therapeutic approach page, or schedule a consultation by clicking the button below.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing.

Herman, J. L. (1992). Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence—From Domestic Abuse to Political Terror. Basic Books.

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). (2022). "Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder." NIMH Website.

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. (2021). PTSD: National Center for PTSD. VA Website.