Shame and Self-Esteem Therapy in Austin, TX

Shame and Self-Esteem Therapy: How EMDR, Ego State Therapy, and Self-Compassion can be Integrated to Reduce Shame and Improve Self-Esteem

Written by Alex Penrod, MS, LPC, LCDC - Licensed Professional Counselor in the state of Texas and Certified Clinical Trauma Professional II

Self-esteem is a fundamental aspect of mental health and well-being, reflecting a person's overall evaluation of their worth and value. For individuals with childhood trauma and PTSD, self-esteem is often severely affected. Trauma, particularly in childhood, can result in deep-seated feelings of worthlessness, shame, and self-blame that persist into adulthood. Therapeutic interventions like Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy, Ego State Therapy, and cultivating self-compassion can be powerful tools to help individuals rebuild self-esteem by addressing the underlying shame and fostering a healthier, more integrated sense of self.

What is Self-Esteem?

Self-esteem is defined as a person’s overall sense of self-worth or personal value. It encompasses beliefs about oneself (e.g., "I am competent" or "I am worthy") as well as emotional states such as triumph, despair, pride, and shame. Self-esteem is influenced by a variety of factors, including childhood experiences, social relationships, and personal achievements. Healthy self-esteem involves having a balanced view of oneself, recognizing both strengths and areas for growth.

How Childhood Trauma Injures Self-Esteem

Childhood trauma, including neglect, emotional abuse, and inconsistent caregiving, can severely damage self-esteem. Trauma disrupts the development of a secure attachment style, leading to internalized beliefs such as "I am unlovable," "I am not good enough," or "I am broken." These beliefs can become deeply ingrained, forming a negative self-concept that persists into adulthood. For individuals with PTSD from adult experiences, re-experiencing trauma and the resulting negative self-beliefs can create a cycle that reinforces low self-esteem.

Factors contributing to low self-esteem in trauma survivors include:

Negative Core Beliefs: Childhood trauma often leads to the development of distorted core beliefs about oneself, such as "I am worthless" or "I am powerless."

Shame and Self-Blame: Survivors may blame themselves for the trauma they experienced, leading to pervasive feelings of shame.

Emotional Dysregulation: Trauma can impair the ability to manage emotions, leading to heightened anxiety, depression, and negative self-evaluation.

Attachment Injuries: Disruptions in early attachment relationships can lead to insecure attachment styles, impacting self-esteem and the ability to form healthy relationships.

Understanding Shame, Parental Introjects, and Therapeutic Approaches to Address Shame

Shame is a powerful and often debilitating emotion that plays a significant role in the psychological experiences of people who have suffered childhood trauma and PTSD. Unlike guilt, which is related to a specific behavior ("I did something bad"), shame involves a negative evaluation of the entire self ("I am bad"). This deep sense of inadequacy, defectiveness, or unworthiness can severely impact a person’s self-esteem, leading to self-destructive behaviors, isolation, and difficulties in forming healthy relationships.

Some Definitions of Shame:

“A painful feeling or experience of believing we are flawed and therefore unworthy of acceptance and belonging.” - Brene Brown

The fear of disconnection

A painful emotion caused by consciousness of guilt, shortcoming, or impropriety. - Webter’’s Dictionary

Transient Shame versus Toxic Shame

Shame can be a transient emotion, but for many with a history of trauma it becomes an enduring aspect of their personality. It’s important to recognize the difference. Humans are social creatures that have historically regulated their behavior through social norms and the acceptance versus rejection of certain behaviors by the group. It would be ideal if people wanted to behave in socially harmonious ways simply out of a desire to treat others well, but in reality the fear of being shamed often plays a significant role in how people conduct themselves.

A person may want to scream at the cashier for giving them incorrect change but may inhibit this impulse when they see others looking at them. Of course some people don’t let this stop them. In this sense, transient shame as a fleeting emotion has a purpose in human behavior and evolution for regulating behavior.

Toxic shame on the other hand becomes an enduring sense of who someone feels they are as a person. Their internal dialogue becomes a rotation of messages such as “I’m just no good,” “I can’t do anything right,” or “People would be better off without me screwing everything up.”

This is an inappropriate and exaggerated level of shame that isn’t in proportion to any specific behaviors, and doesn’t offer the opportunity to simply adjust a few things to feel like a worthy person again. It becomes a terminal and fixed reality many perceive as unchangeable. “Just my lot in life,” is how it can come to feel. To overcome such an intrenched belief system often requires intensive work over a longer time frame.

Shame as a Form of Trauma

Shame can be equal to trauma, if not more destructive in its impact, because it is a form of trauma that signals threat to our social survival. Our brains perceive judgment and rejection from others as a threat to survival because rejection from the group has historically meant severe consequences for an individual. Having the group turn on you is usually an emotional experience in modern times, but if we recall our history it often meant death in ancient times.

When we feel on the edge of being exiled socially our bodies respond with a cascade of stress hormones and fight, flight, freeze responses. As John Bradshaw explains, if shame is chronically activated we can develop of form of complex trauma in the relational context. Perfectionism and overcompensating behaviors can lead to burnout and exhaustion without ever addressing the underlying shame.

“Prolonged shame states early in life can result in permanently dysregulated autonomic functioning and a heightened sense of vulnerability to others. Their lives are marked by chronic anxiety, exhaustion, depression and a losing struggle to achieve perfection.” - John Bradshaw

Parental Introjects and Their Impact on Shame

A common source of shame in those with childhood trauma stems from parental introjects—internalized voices or beliefs derived from early caregivers. When a child experiences criticism, neglect, or emotional abuse, they often internalize these negative messages as truths about themselves, creating a "parental introject" that perpetuates shame and self-criticism. Addressing shame and these toxic introjects in therapy is crucial for improving self-esteem and emotional well-being.

Parental introject beliefs are often carried into adulthood as if they were the person’s own beliefs and voice. It can be hard to understand at face value how this could be adaptive, but as a child, helpless to escape or choose a different caregiver, learning how to anticipate criticism and abuse internally serves to guide the child on how to avoid it externally. It can also reduce the emotional impact if the child can internally criticize themselves before someone else gets the chance to, providing a sense of control. Unfortunately, this adaptation continues beyond its usefulness and can become crippling in adulthood.

Negative Self-Talk: Parental introjects often present as critical inner voices that echo negative messages received in childhood, such as "You’re not good enough," "You’ll never succeed," or "You’re a burden."

Reinforcement of Shame: These introjects reinforce shame by perpetuating a narrative of worthlessness and failure, making it difficult for individuals to develop self-compassion or a positive self-concept.

Obstacles to Healing: Parental introjects can create resistance to therapy and healing because the individual may unconsciously align with these internalized negative beliefs, feeling undeserving of compassion or change.

A note on parental injects: For parents reading this and wondering if they are guilty of it, it’s important to remember that although you may have been part of passing it on, you are likely not the origin of shame. Trauma and shame travel down family lineages just like eye color or facial features.

The concept of parental introjects may seem like a scathing indictment against individuals, but the metaphor I like to use to put it into perspective is that of the common cold. If you sneeze on someone and give them a cold, you are not responsible for the fact that you had a cold, and you we’re most likely not patient zero.

But if you recognize you have a cold, it is your responsibility to stop sneezing on others and take care of yourself so you can become healthy again. Shame and trauma in the family system is just like this, someone has to take responsibility at some point and stop the transmission to the next generation. Will it be you?

It’s also important to recognize that not all shame messages come from parents. For children and adolescents, the opinion of their peers and feeling accepted is often a fundamental aspect of their life. Being bullied, targeted, or publicly shamed by teachers or coaches can lead to equal if not more harmful results than being criticized or verbally abused in the home.

With social media and internet presence being central to the lives of children and teenagers today, what used to be an 8 hour ordeal of going to school each day has now become a 24-hour a day opportunity to be the victim of harassment and bullying. These wounds can last long into adulthood.

Responses to Shame that can Bring on More Shame

Although the origins of shame and low self-esteem often begin in childhood, the coping strategies and defenses employed to either compensate or numb away the feelings can put people on a trajectory to reinforce their shame as an adult in vicious cycle patterns.

Common examples of shame based coping strategies:

Substance Use: Early substance use is often an indicator of relief seeking.

Drugs and alcohol provide a powerful escape to overcome anxiety, give false confidence, find belonging among like-minded friends who are also struggling, or simply obliterate the emotions and thoughts for a while.

This leads to poor functioning and negative consequences in life, reinforcing a negative self-concept of “I can’t do anything right,” or “I’m such a loser,” that fuel even more substance use.

Behavioral addictions such as gambling, pornography, shopping, etc., can all fall into a similar pattern.

Eating Disorders: If shame centers around body image or sports performance, with perfection in these areas being used as a compensatory strategy, eating disorders can develop.

The underlying belief can be, “If I had the perfect appearance or performance I would not be vulnerable to shame.”

Although people with eating disorders often truly believe they need to change their bodies and feel they are flawed regardless of reassuring feedback from others, they are often very secretive about their eating behaviors and feel shame and defensiveness if they are confronted.

This is a very difficult dilemma, to feel intense shame about such a core aspect of yourself and also feel shame, judgment, and isolation about what you are trying to do about it.

Self-Harm: People with histories of childhood trauma sometimes find that self-harm offers a way to regulate their emotions and release endorphins that temporarily boost their mood.

Harsh and critical parental introjects may also encourage self-harm as a way to be punished for being shameful.

Many people who self-harm report feeling a “calm after the storm” after self-harming that can be blissful but short in duration.

Self-harm often becomes a source of shame as others react with fear, judgment, disgust, or rejection, further fueling the need to employ the very strategy that brought on the shame.

Perfectionism: While perfectionism may seem like a healthier alternative to the previous strategies, it is often just as harmful because it usually goes unnoticed, can be exploited by others, and the achievements are rewarded, encouraging more and more effort.

Someone struggling with perfectionism may obtain multiple degrees, be a star athlete, try be everyone’s best friend, and work 100-hour work weeks, yet live in a constant state of self-criticism, anxiety, and berate themselves over minor mistakes.

Success can hardly be enjoyed under these conditions and the bar is continually set higher to impossible standards, leading to more shame and eventual burnout.

Compulsive Caretaking: Compulsive caretaking is similar to perfectionism but focused on being perfect at caring for and “saving” others who need rescuing.

The caretaker’s focus on the other serves a dual role of allowing them to be distracted from how they feel about themselves and having the hope that if they could just help this person enough it would redeem them or render them “good enough.”

It fills a void and offers an illusive sense of purpose that can’t quite be achieved. Rather than focusing inward where things feel out of control, a sense of control is derived from trying to manage outcomes for others.

While each of these strategies can take someone down a vastly different road in life with a variety of consequences, at their root is core shame. To truly intervene on these cycles requires much more than changing the behavior. Healing shame at a core level is vital for long-term success and resilience against falling back into the loop again.

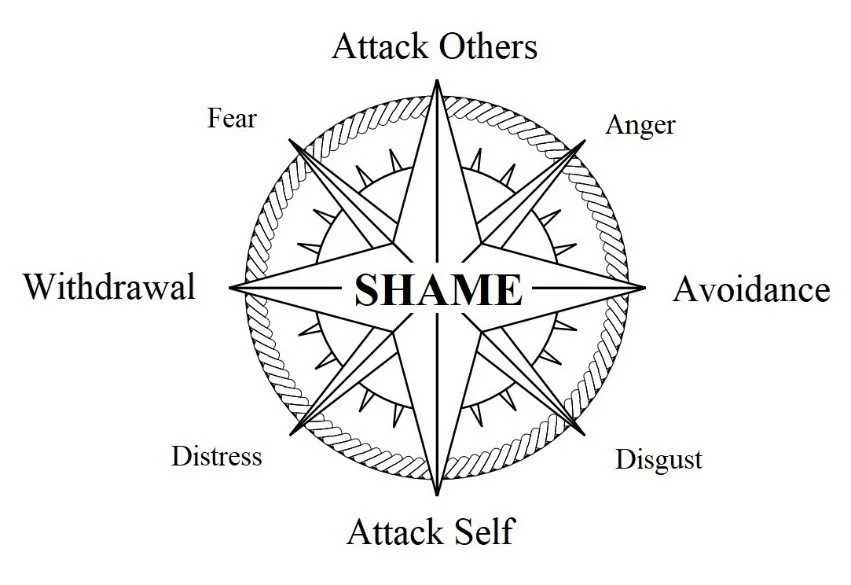

The Shame Compass

Understanding the Shame Compass

Shame is a powerful and overwhelming emotion that can drive us to react in ways we may not fully understand. The shame compass offers a helpful framework to understand the different ways we respond when we experience shame. It highlights four common directions: attack self, attack others, withdraw, and avoid. By recognizing these responses, we can begin to shift our patterns of behavior and work towards healing.

Attack Self

In this direction, shame turns inward. People may experience the harsh inner critic that tells them they’re not good enough, unworthy, or flawed. This self-attacking response can lead to feelings of depression, self-hatred, or even self-harm. It often stems from deep-rooted beliefs of being inherently defective, which can be challenging to overcome without specialized therapy.

Attack Others

When shame is externalized, it can manifest as attacking others. This response seeks to deflect uncomfortable feelings of shame by blaming or criticizing others. A person might become defensive, angry, or aggressive, shifting the focus away from their own vulnerabilities. While it can provide temporary relief, this approach often damages relationships and leaves unresolved emotions festering underneath.

Withdrawal

Withdrawal is a retreat from others in an attempt to avoid the painful feelings of shame. This can look like pulling away from social interactions, isolating, or shutting down emotionally. People who respond with withdrawal may feel a deep sense of hopelessness or fear that their flaws will be exposed, leading them to disconnect from those who might offer support.

Avoid

The avoid direction focuses on distraction and numbing as a way to escape the discomfort of shame. This can take the form of substance use, overworking, compulsive behaviors, or any other activity that provides a temporary escape. While avoiding shame might offer short-term relief, it prevents true healing and often leads to a cycle of avoidance and emotional disconnection.

Each individual may have a primary direction they go in when confronted with shame, but the full range of directions is often experienced, usually in a sequence. Relationships can become toxic when there is a pattern of attacking the other person, withdrawing into remorse and self-hatred, attacking self, then launching into avoidance with frantic efforts to “make it up” to the other person. Efforts at repair are often short lived and tensions build again because the underlying wounds are never dealt with. Abuse is not excusable or justified and it occurs for many other reasons than shame, but the above example is a common pattern between partners with unhealed trauma.

Using Ego State Therapy, Self-Compassion, and EMDR to Address Shame

Three therapeutic approaches—Ego State Therapy, Self-Compassion, and EMDR—are particularly effective for helping clients process and transform shame into self-acceptance and empowerment.

1. Ego State Therapy

Ego State Therapy involves working with different parts of the self, or "ego states," that may hold specific emotions, memories, or beliefs formed in response to childhood experiences, including shame and parental introjects. This therapy helps clients understand and heal these parts, facilitating a more integrated and compassionate sense of self.

Identifying Shame-Based Parts: Ego State Therapy helps clients identify parts of themselves that carry the burden of shame or parental introjects, such as the “critic" part that constantly judges a "wounded child" part that feels unworthy. By acknowledging these parts, clients can begin to understand where these feelings originated and how they were formed as protective responses to early experiences.

Transforming the Inner Critic: Ego State Therapy can transform the "inner critic" (a common parental introject) into a more supportive and balanced voice. By understanding that this critic was initially formed to protect against perceived threats or rejection in childhood, this part can often become willing to update its job duties and tone to be appropriate for the present context.

Re-parenting and Nurturing Wounded Parts: Clients are guided in providing care, understanding, and compassion to the parts of themselves that have internalized shame. This process of "re-parenting" involves creating a safe internal environment where wounded parts can express their needs and feel heard.

Creating a Safe Internal Environment: By resolving internal conflicts and fostering cooperation among ego states, clients can develop a safer, more harmonious internal environment, which supports a healthier self-esteem.

Goal: Ego State Therapy helps reduce shame by integrating and healing the parts of the self that hold onto it. This approach fosters a compassionate, unified self-concept, where negative introjects are replaced with nurturing, supportive self-talk.

How Ego State Therapy Improves Self-Esteem:

Promotes self-compassion and understanding of different parts of the self.

Integrates fragmented parts into a more cohesive and positive self-identity.

Reduces self-blame and shame by reframing the trauma response as a survival mechanism.

2. Cultivating Self-Compassion

Self-Compassion is a therapeutic approach that involves “treating oneself with the same kindness, understanding, and care that one would offer to a close friend” - Kristen Neff. For trauma survivors, cultivating self-compassion is essential for overcoming shame and negative self-beliefs.

Mindful Awareness of Shame: Self-compassion begins with becoming mindfully aware of shame without judgment. This means recognizing feelings of shame as they arise and understanding their origins, often rooted in past trauma or unmet emotional needs.

Self-Compassion Practices: Techniques such as self-compassionate letter writing, mindfulness exercises, and guided meditations help clients develop a kinder, more understanding relationship with themselves. These practices can counteract the harsh self-criticism that stems from parental introjects.

Reframing the Shame Narrative: Self-compassion involves reframing the narrative around shame, moving from "I am bad" to "I am a human being who has experienced pain." This shift allows individuals to see themselves through a lens of empathy rather than condemnation.

Goal: By cultivating self-compassion, clients can soften their internal dialogue, challenge harsh parental introjects, and gradually replace shame-based narratives with ones that are more supportive and self-affirming.

How Cultivating Self-Compassion Improves Self-Esteem

Creates a more balanced internal voice capable or recognizing strengths alongside shortcomings and encouraging problem solving rather than rumination and self-deprecation.

Promotes taking new actions that will build self-esteem by providing evidence of competence, values, and esteemable deeds.

Allows for more risk taking and resilience against set-backs because self-compassion allows for mistakes, takes them in stride, and doesn’t punish mercilessly.

3. Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR)

EMDR is an evidence-based trauma therapy that uses bilateral stimulation (such as eye movements) to help clients process and integrate traumatic memories and the negative self-beliefs attached to them. EMDR is particularly effective in shifting belief systems instead of just desensitizing memories.

Targeting Shame-Related Memories: EMDR targets specific traumatic memories that have led to shame and self-criticism, helping to desensitize the emotional charge of these memories. This process involves identifying the core belief associated with the memory (e.g., "I am unlovable") and reprocessing it to form a more adaptive belief (e.g., "I am worthy of love and care").

Healing Attachment Wounds: EMDR can address attachment injuries by targeting memories of neglect, rejection, or abandonment, allowing clients to reprocess these experiences and internalize a sense of safety and worth.

Installing Positive Cognitions: During EMDR, clients are guided to replace negative beliefs rooted in shame with positive cognitions that reflect their inherent worth. By reinforcing these positive beliefs, EMDR helps transform the way individuals perceive themselves.

Reducing the Power of Parental Introjects: EMDR can also be used to specifically target and desensitize the emotional impact of parental introjects. By processing the original experiences where these introjects were formed, clients can reduce their intensity and influence, making it easier to cultivate a more compassionate inner voice.

Goal: EMDR helps rewire the brain’s response to traumatic memories and parental introjects, diminishing their power to perpetuate shame. This allows clients to develop healthier, more positive self-beliefs and improve overall self-esteem.

How EMDR Improves Self-Esteem:

Replaces negative self-beliefs with adaptive, empowering beliefs.

Reduces the emotional distress associated with traumatic memories.

Fosters a more balanced and positive self-concept by integrating new, healthier beliefs.

Conclusion

Shame and perfectionism, especially when reinforced by parental introjects, can be a significant barrier to healing for individuals with childhood trauma and PTSD. Therapeutic approaches like Ego State Therapy, Self-Compassion, and EMDR offer effective strategies to address and transform shame, helping clients rebuild a positive self-concept and enhance self-esteem. By integrating these approaches, individuals can learn to see themselves through a lens of compassion, develop a more unified sense of self, and ultimately experience a deeper sense of worth and self-acceptance.

As a trauma therapist, I’ve facilitated workshops on shame and worked with clients to build self-esteem in therapy for many years. Although reducing the more immediate symptoms of trauma is paramount, one of my favorite parts of therapy is seeing clients heal at a core level and begin living their lives in ways they couldn’t have dreamed of before. If you’re interested in learning more, schedule a free consultation with me and we can discuss your goals when it comes to shame and self-esteem.

Schedule a Free Consultation

References

Brown, B. (2012). Daring Greatly: How the Courage to Be Vulnerable Transforms the Way We Live, Love, Parent, and Lead. Gotham Books.

Brown, D., & Elliott, D. S. (2016). Attachment Disturbances in Adults: Treatment for Comprehensive Repair. W. W. Norton & Company.

Davis, S. (2019, April 11). The Neuroscience of Shame. CPTSDfoundationorg.

Gilbert, P. (2010). The Compassionate Mind: A New Approach to Life's Challenges. New Harbinger Publications.

Herman, J. L. (1992). Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence—from Domestic Abuse to Political Terror. Basic Books.

Porges, S. W. (2017). The Pocket Guide to the Polyvagal Theory: The Transformative Power of Feeling Safe. W.W. Norton & Company.

Schwartz, R. C. (2020). Internal Family Systems Therapy, Second Edition. Guilford Press.

Shapiro, F. (2018). Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) Therapy, Third Edition: Basic Principles, Protocols, and Procedures. Guilford Press.

van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Penguin Books.

Watkins, J. G., & Watkins, H. H. (2007). Ego State Therapy. W. W. Norton & Company.